Necessity of this Introduction – The two Historians of Kentucky – The original Indian claimants of Kentucky – Treaties with them – The Pioneers – Dr. Walker – John Finley – Daniel Boone – The “Long Hunters” – The Surveyors – The first man burned in Kentucky – James Harrod – Stations of Boonesborough and Harrod;s Town – Other Stations – Difficulties and dangers of the Emigrants – James Rogers Clark – Takes Kaskaskias and Post St. Vincent’s – Battle of Blue Licks – Expedition of Clark – Kentucky a State – Gen’l. Wayne’s Victory – Treaty of Greenville – General Peace.

Before we attempt to sketch the early religious history of Kentucky, it will be necessary, for the better understanding of the subject, rapidly to trace the chief events connected with the first settlement of this Commonwealth. Our plan will call for and permit only a very brief summary. Those who may wish a more detailed account are referred to the two Histories of Kentucky written by Humphrey Marshall and Mann Butler.[1] The latter, though more concise than his predecessor, will be found in general more accurate, more impartial, more learned, and more satisfactory. His style also, though far from being faultless, or even always grammatical, is more simple and in better taste than that of Marshall, who often indulges in fustian and school-boy declamation.

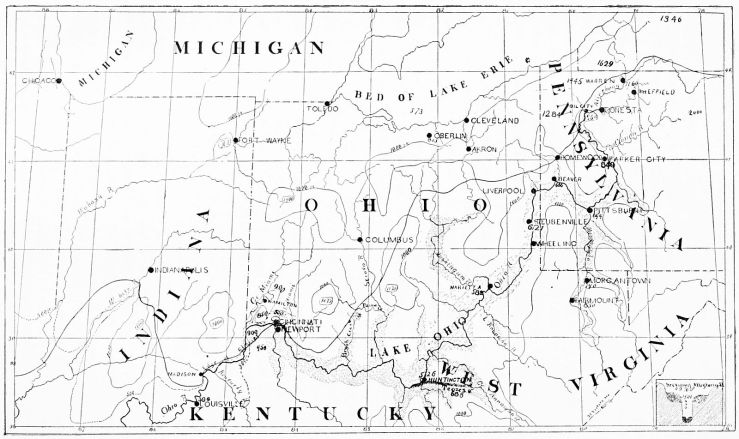

Kentucky is the oldest of all the States west of the Allegheny Mountains. She became a State and was admitted into the Union in 1792, four years sooner than Tennessee, and ten years before Ohio. The first hardy adventurers who travelled westward came to Kentucky; and the first Catholic missions in the west, if we except those at the French stations on the Wabash and the Mississippi, were those established in Kentucky. So that, both in a political and in a religious point of view, Kentucky pioneered the way for the other western States of our confederacy.

Nor does the interest which attaches to her early history stop here. This history is rich in examples of lofty daring, hardy adventure, and stirring incident. It tells of dangers encountered, and of difficulties overcome, which would have appalled the stoutest hearts. It speaks of the deeds of an iron race of pioneers, now fast disappearing from the theatre of life, who fed on difficulties and dangers, as their daily bread, and were thus nerved for the difficult mission they had to accomplish. They never faltered in their purpose for a moment, but ceaselessly marched on, planting farther and farther in the unreclaimed forests the outposts of civilization. When Kentucky had been settled by a white population, we find many of them moving still farther westward, with Daniel Boone, never satisfied unless their houses were built in the very midst of the waving forests!

The land of Kentucky – or, as the Indians called it, Kantuckee – seems not, within the memory of the white man, ever to have been permanently settled by any Indian tribe. The hunters from North Carolina and Virginia, who visited it after the year 1767, could discover no trace of any Indian inhabitants.[2] It was a kind of neutral territory, and a common hunting-ground for the various Indian tribes. It became also, from this very circumstance, a great Indian battleground. The Miamis, Shawnees, and Illinois, from the banks of the Miami, the Scioto, and the Illinois rivers, of the north; and the Cherokees and Tuscaroras from the south, repeatedly met and struggled for the mastery on the “dark and Bloody Ground.” Thus it happened, that various Indian tribes successively swept over Kentucky, leaving no trace of their passage behind them. This also explains to us the many conflicting claims to the proprietorship of its territory put in by the different Indian nations.

From an early period of their history, the Indian tribes of the northwest had been seeking to conquer or exterminate one another. The most powerful of these was the great confederation of the Five Nations of New York; of which the Mohawks, or Iroquois – as the French historians style them – were the principal. Like the ancient Romans, they were in the habit of incorporating into their own body the various tribes whom they successively subdued. They gradually extended their conquests towards the west and the south. As early as 1672, after having subdued the Indian tribes on both sides of Lake Huron, they had conquered the Chawanons, or Shawnese, on the Illinois river; and in 1685, the Twightees, subsequently called the Miamis. In 1711, they conquered and incorporated into their own body the Tuscaroras of the south, who from that period constituted the sixth nation of this powerful confederacy.[3]

This confederation claimed by right of conquest the proprietorship of Kentucky, and of all the lands lying on both sides of the Ohio river. Governor Pownal testifies, that the Six nations were in actual possession of all these lands at the peace of Ryswick, in 1697.[4] In their treaty with the British Colonies, in 1744, they put in this claim.[5] They had already put themselves and their vast territories under the protection of the British government, in the year 1701, and again in 1726:[6] AND IN THE TREATY OF Fort Stanwix, in 1768, they had ceded their rights to the British government, for the sum of £10,460 7s. 6d., paid them by Dr. Franklin.

Subsequently, after the conclusion of the French and British war of 1755-1763, the Six Nations seem to have practically relinquished all claim to Kentucky and to the whole territory of the northwest. The two great confederacies of the Miamis and of the Illinois appear, from the banks of the Scioto to those of the Mississippi. The former occupied part of Ohio and the whole of Indiana; the latter, the present State of Illinois. This statement is confirmed by General Harrison,[7] who farther remarks, that the Miamis were the original occupants of the soil, and that the other tribes were viewed as intruders. The Six Nations were called the northern, and those of whom we have just spoken, the western, confederacy. By these two powerful confederations the minor Indian tribes were either successively exterminated, or driven farther into the wilderness.

The right of proprietorship to the soil of Kentucky was obtained by different treaties with the Indian tribes, who successively laid claim to it. The principal of these treaties were: that of Fort Stanwix with the Six Nations, in 1768, already alluded to; that of Lord Dunmore with the Shawnese, in 1744; and that of Col. Henderson with the Cherokees, who ceded their rights to the soil, for the consideration of £10,000, in the year 1775. This last treaty interfered greatly with those previously made; and the conflicting claims which it originated were a fruitful source of litigation among the early emigrants to Kentucky. It was finally set aside and declared illegal by the legislature of Virginia, which however, by way of compensation, assigned ample territory to the Henderson Land Company, in the northwestern part of Kentucky.[8]

The first settlement of Kentucky by the white people was commenced under the circumstances of great difficulty and danger. The first who visited it were either hunters or mere roving adventurers. As early as the year 1747, Dr. Walker of Virginia led a party of hardy adventurers as far as the banks of the Cumberland river, a name which he gave to that stream, after the “bloody Duke” of England, in place of its old denomination of Shawanee. It is also known, that in the year 1767, the country was visited by John Finley, with a party of hunters from North Carolina; though no written account of this visit has been preserved. Its only result seems to have been to stimulate others to enter on the same perilous career of adventure.

Among those to whom Finley related the thrilling story of his visit to this hitherto unexplored region, was a man, whose life is identified with the early history of Kentucky, and whose name shines conspicuous among the pioneers of the west. For bold enterprise and lofty daring; for unfaltering courage and utter contempt of danger; for firmness of purpose and coolness of execution; for all the qualities necessary for a successful pioneer, few men deserve to rank higher than Daniel Boone. He was the very man for the emergency. His soul was fired with the prospect opened to him by the relation of Finley; and he entered upon the new career which lay before him, with all the ardour of his soul – an ardour which was however qualified by the cool determination to do or to die.

On the first day of May, 1769, Daniel Boone, accompanied by John Finley, John Stewart and three others, left his residence on the Yadkin river, in North Carolina, with the determination to explore Kentucky. On the 7th of June, he reached Red river, a branch of the Kentucky river. From an eminence, he descried the beautiful level of Kentucky, about Lexington; and his soul was charmed with the prospect. He represents the whole country as swarming with buffalo, deer, elk, and all kinds of game, and filled with wild beasts. He continued hunting with his companions until the 22nd of December, soon after which John Stewart was killed by the Indians; the first white man known to have fallen by their hands in Kentucky. His comrades, probably alarmed by this circumstance, returned to their homes in North Carolina; but Daniel Boone, with his brother who had lately come out, remained in Kentucky during the winter. He pitched his camp on a creek in the present Estill county, called, from this circumstance, Station Camp Creek. Here he continued until the following May, undisturbed by the Indians, who seldom visited Kentucky in the winter.[9] He then returned to his friends on Yadkin river.

In this same year, 1769, Col, James Knox led out a party of about forty hunters through the unexplored regions of Tennessee and Kentucky. In Kentucky, nine of this party penetrated as far as the Green and Cumberland rivers, and were designated “the Long Hunters,” from the length of time they were absent from their homes.[10]

The bounty lands awarded by the British government to those who had served in the war against the French, furnished another keen incentive to emigration. For, though the royal proclamation granting the bounty, forbade that the lands should be laid off on the Ohio river, yet its prohibition was disregarded. Surveyors, employed by the claimants of these bounty lands, penetrated to all parts of Kentucky. The most conspicuous of these land surveyors were Thomas Bullit and Hancock Taylor, who came out to Kentucky from Virginia in 1773. On their route they were overtaken by the M’Afees, whose names are so closely connected with the history of the early settlement of our State.[11] Bullit was elected Captain of the party, which proceeded to mark off the site of the present city of Louisville, in August, 1773.

During the same year, James Douglass, another surveyor, visited Kentucky. He was the first man who discovered the celebrated collection of mammoth bones, in the place known since by the name Big Bone Lick. “Douglass formed his tent poles of the ribs of some of the enormous animals, which formerly frequented this remarkable spot, and on these ribs blankets were stretched for a shelter from the sun and the rain. Many teeth were from eight to nine. And some ten feet in length; one in particular was fastened in a perpendicular direction in the clay and mud, with the end six feet above the surface of the ground; an effort was made by six men in vain to extract it from its mortise. The lick extended to about ten acres of land, bare of timber, and of grass or herbage; much trodden, eaten, and depressed below the original surface, with here and there a knob remaining to show its former elevation.”[12]

About the year 1774, another surveyor, Simon Kenton, with two companions, landed a few miles above Maysville, or Limestone, as it was then called. This party penetrated to May’s Lick, and visited the Upper and Lower Blue Licks. They saw immense herds of Buffalo, in the vicinity of the licks. On returning to his camp, near May’s Lick, from one of his exploring expeditions, Kenton found it sacked and burned by the Indians; and, at a little distance from it, he discovered the mangled remains of Hendricks, one of his companions, who had been tied to a stake and burned. He was the first and the last white man who suffered this cruel manner of death at the hands of the Indians on the soil of Kentucky.[13]

The parties who had hitherto visited Kentucky were either hunters, land surveyors, or mere adventurers. No attempt had as yet been made to settle down on the soil and to establish regular colonies. On the 25th of September, 1773, Daniel Boone attempted to remove five families to Kentucky, with a view to their permanent location in the territory which he had already explored. But he had not advanced far when, according to his own account, “the rear of his company was attacked by Indians, who killed six men and wounded one.”[14] The party returned to their homes, in North Carolina, and the attempt was given over for the present.

Another hardy adventurer from Virginia, was more fortunate. James Harrod came out to Kentucky with several families, in the year 1774. He built the first log cabin in Kentucky, on the site of the present town of Harrodsburgh, then called Harrod’s Town. This colony was soon dispersed by the Indians; but, after a brief interval, it was re-established under more favorable auspices.[15]

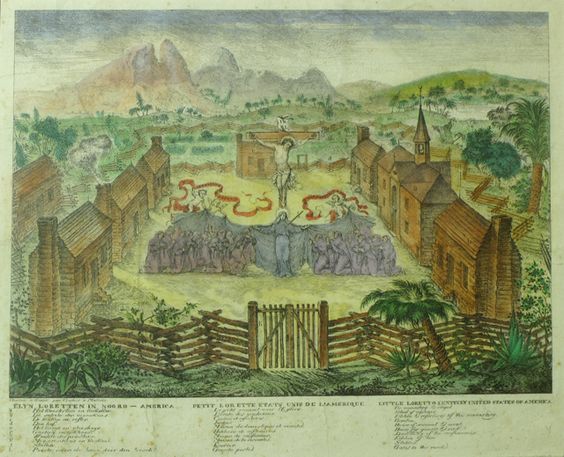

Early in 1775, Daniel Boone again visited Kentucky, in the capacity of guide to a party sent out by the Henderson Land Company, which had purchased the Cherokee title to all the lands south of the Kentucky river. The party was often attacked by the Indians, but finally succeeded in reaching the Kentucky river. To protect themselves from Indian invasion, they immediately set about erecting a fort, which was called Boonesborough. It was commenced on the 1st of April of that year, and completed on the 14th of June following. This was the first fort erected in Kentucky. It consisted of a stockade, with block houses at the four angles of the quadrangular inclosure.[16]

The next fort erected was that at Harrod’s Town. The colony in the vicinity of this place had been greatly strengthened by a party led out from North Carolina, by Hugh McGary, in the fall of 1775. At Powell’s valley he had united his party to another conducted by Daniel Boone; and the whole body numbered twenty-seven guns, or fighting men, besides women and children. The parties again divided on reaching Dick’s river; that under Boone repairing to Boonesborough, and that under McGary, to Harrod’s Town. The fort in this latter place was commenced in the winter of 1775-6.[17]

Whenever a colony was planted, there a fort was also erected, as a protection against the Indians. They were called Stations. These multiplied in proportion as the new territory became settled. The principal and most ancient of them, besides those already named, were: Logan’s Station, established by Col. Benjamin Logan, about the same year as that at Harrod’s Town, at the distance of one mile from the present town of Stanford, in Lincoln county; Floyd’s Station, on Beargrass Creek, about six miles from Louisville, and another in Lexington.

Many were the difficulties and terrible the dangers encountered by the first emigrants to Kentucky. They carried their lives in their hands: the Indians gave them no rest day or night. From the date of the first settlement in 1774, to that of Wayne’s decisive victory and the subsequent treaty of Greenville, in 1795 – a period of twenty-one years – Kentucky was a continued battle-ground between the whites and the Indians, the latter ceaselessly endeavoring to break up the colonies, and the former struggling to maintain their position. The savages viewed with an evil eye the encroachment on their favourite hunting grounds, and employed every effort to dislodge the new comers. To effect their purpose, they resorted to every means of stratagem and of open warfare. Their principal efforts were, however, directed against the forts, which they rightly viewed as rallying points of the emigrants. For nearly four years they besieged, at brief intervals, the forts of Harrod’s Town and Boonesborough, especially the former, which they made almost superhuman exertion to break up.

The colonists were often reduced to the greatest straits. Their provisions were exhausted, and all means of obtaining a new supply seemed hopelessly cut off. Their chief resource lay in the game with which the forests abounded. But hunting was hazardous in the extreme, while their wily enemies lay in ambush in the vicinity of the forts. The hunters were often shot down, or dragged into a dreadful captivity, with the prospect of being burned at the stake, staring them in the face. Did they attempt to cultivate the soil, the husbandmen were often attacked by the Indians. The labourers in the field were under the necessity of being constantly armed: they were generally divided into two parties, one of which kept guard, while the other cultivated the soil. But during the four years’ siege, above referred to, even this method of tilling the land became too hazardous, and was, at least to a great extent, abandoned.

Besides, their ammunition was often exhausted, and the obtaining of a new supply was extremely difficult and dangerous. The road to the old settlements lay through a wilderness beset with lurking savages. All these difficulties taken together, became truly appalling. Still the hardy pioneers were not cast down. They were struggling for their new homes, for their families, for their very existence. Prodigies of valour were achieved by individuals, and by small parties, to detail which would greatly exceed the limits of this brief summary.[18] It was the heroic age of Kentucky.

But the rude military tactics of the savage could not cope with the superior organization and higher civilization of the white man. Succours continued to pour into the stations, from Virginia, North Carolina and Maryland, in spite of all Indian opposition. In 1775, there arrived in Harrod’s Town a man who was destined to exercise a powerful influence on the rising destinies of Kentucky and of the whole west. James Rogers Clark was a native of Virginia, whence he emigrated to join the bands of hardy adventurers who were seeking their fortunes in the west. He was young, bold, and adventurous; was active in body and mind; and was gifted with great coolness, forecast, and military talent.

In the fall of the year, 1775, Clark returned to Virginia, but he revisited Harrod’s Town in the following spring. A meeting of the citizens was held, and he and Gabriel John Jones were ap-pointed delegates to the legislature of Virginia. They succeeded in obtaining from the Governor and Council of that Commonwealth a loan of 500 pounds of gunpowder, which Clark was charged to transport to Harrod’s Town. Clark executed this difficult commission with wonderful intrepidity and success. After having been pursued through almost the entire journey by the Indians, who compelled him to conceal the gunpowder for some time near Maysville, or Limestone, he finally succeeded in delivering it safely at Harrod’s Town. The drooping spirits of the garrison rallied on receiving this most fortunate supply, which, had it fallen into the hands of their enemies, would have been employed for their destruction.

The active mind of Clark soon led him to the conviction, that unless some decisive blow were struck, the infant colonies could not hope long to struggle successfully against their savage invaders. He determined to carry the war into the heart of their own territory, and to wrest, if possible, from the hands of the British the military stations of Kaskaskias and St. Vincents, or Post Vincennes. These his quick eye soon discovered were the great rallying points of the Indian invaders. Accordingly, he obtained a Colonel’s commission from the Commonwealth of Vir-ginia, with men and military supplies for the expedition: The commission was dated January 2nd, 1778. It was drawn up by Patrick Henry, the Governor of Virginia, who gave Colonel Clark two sets of instructions: one public, ordering him to repair to Kentucky for its defence; and the other private, directing an attack on the British Post of Kaskaskias. The war of the Revolution was then raging; and the success or failure of Clark’s expedition was destined to have an im-portant bearing on the question, whether Great Britain or the United States should be able to claim the proprietorship of the northwest.

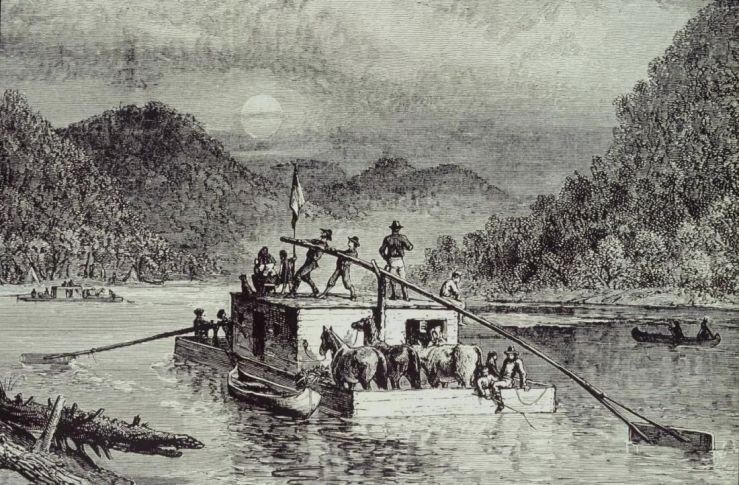

Col. Clark showed by his conduct that the confidence reposed in him was not ill-placed. He conducted the expedition with singular prudence and secrecy. He landed his small army near fort Massac, on the Ohio river; marched through Illinois; and, on the fourth of July, 1778, he took Kaskaskias by surprise, without shedding a drop of blood! On the sixth of July, he detached Col. Bowman with a company of men, who surprised and captured the neighbouring military post of Cahokias.[19]

Col. Clark determined to follow up the advantages thus secured. After a long and painful march through Illinois, in the most inclement season of the year, he appeared, on the 23rd of February, 1779, with 170 men, before Post St. Vincent’s, on the Wabash, then also in possession of the British. He compelled the British commandant, Hamilton, to surrender at discretion, after a slight previous skirmishing.* Thus, were the British driven from the northwest, by a mere handful of men, under a gallant and skillful commander. And thus also were the great centres of Indian invasion broken up.

Still., notwithstanding this terrible blow struck in the strongest rallying points of the northwest, the Indians, especially the Miamis and the Shawnese, continued to carry on the war with unabated fury, against the white settlers of Kentucky. They united their forces at Chilicothe, and determined to strike one more blow for the recovery of their favourite hunting grounds, which they beheld fast escaping from their grasp.

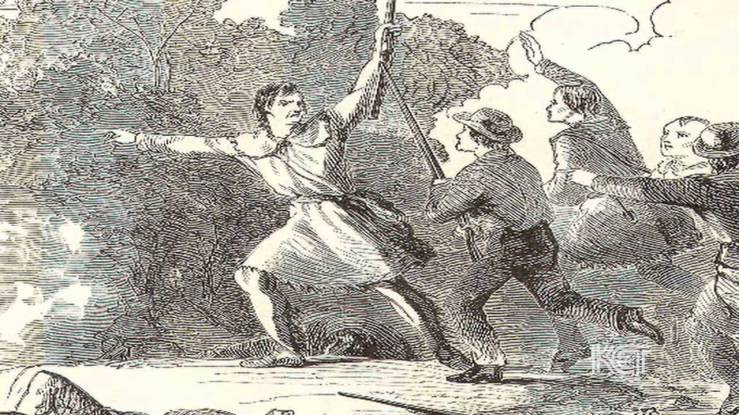

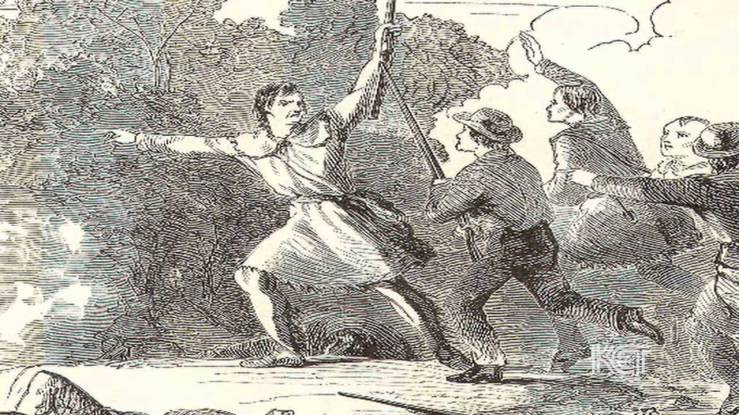

On the 14th of August, 1782, an army of about 500 warriors suddenly appeared before Bryant’s Station, twelve miles from Lexington. So cautious had been their movements, that they made their appearance in the very heart of Kentucky without exciting any alarm. They closely encompassed the place, killing or driving away the cattle and horses, and shooting down or taking prisoners chance stragglers from the station. The siege continued for only two days; for happily on the first appearance of the savages, a few intrepid men had escaped, who carried the alarm to the neighbouring stations of Lexington, Boonesborough, and Harrod’s Town; and also to Logan’s Station. So prompt were the movements of the men in these stations, for the succor of their brethren, that on the 18th of August, a force of 182 chosen men from Lexington, Boonesborough, and Harrod’s Town, assembled at Bryant’s Station. The Indians, anticipating, or cognizant of this movement, had already fled. They were hotly pursued to the Lower Blue Licks, a distance of about 40 miles, where they were speedily overtaken. Daniel Boone and some other officers, fearing an ambuscade, endeavored to check the ardour of the pursuit, in order to await the arrival of reinforcements under Col. Benjamin Logan from Logan’s Station. But this wise course was prevented by the imprudent impetuosity of Major Hugh M’Gary, who, plunging his horse into the Licking river, cried out, with a loud voice, that “all who were not cowards should follow him, and he would show them where the Indians were.”

The whole body of the pursuers shared in his impetuosity, and followed after him in disorder. But they had not advanced more than a mile, when they received, throughout their whole front line, a murderous volley from the Indians, who lay concealed in a deep ravine, extending on both sides of the road at right angles to it. The ranks of the white men were thrown into confusion, and, though they fought with desperation, could not withstand the assault for more than a few minutes. They fled precipitately, the Indians following them with loud shouts and uplifted tomahawks. Many were killed in the attempt to re-cross Licking river. The route was complete, and the Indians pursued them for many miles, killing or taking prisoners the straggling parties whom they were able to overtake.

Never, in the whole annals of Indian warfare in Kentucky, had the white people experienced so overwhelming a defeat. Besides the wounded, about sixty of them were killed, and seven taken prisoners; most of them from Harrod’s Station. Among those slain were Col. Todd from Lexington, and Majors Trigg, McBride, and Harland, from Harrod’s Town. Major M’Gary escaped. [20]

Shortly after the action, Col. Benjamin Logan reached the battle ground with 450 chosen men; but only in time to bury the mangled bodies of the dead. The Indians had already fled into the interior of Ohio. Had the pursuing army patiently awaited his arrival, the disastrous defeat of the Blue Licks might have never occurred. But petty jealousies among the officers, and their desire to win the laurels of victory without the presence and assistance of their senior officer, Col. Logan, prevented their taking the prudent advice of Daniel Boone: and bitterly did they rue their rashness, when it was too late.[21]

In the midst of the despondency occasioned by this ruinous defeat, all eyes were turned on Col. James Rogers Clark, who had recently been promoted to the rank of General. He immediately called a meeting of the superior officers, at the Falls of the Ohio river; and it was unanimously resolved to organize a large body of mounted riflemen, for the pupose of attacking the Indian towns in the interior of Ohio,

On the last day of September, 1782, 1000 mounted riflemen appeared at the appointed place of rendezvous, the mouth of Licking river, under the command of Cols. Floyd and Logan, who were the officers next in rank to General Clark. The expedition proceeded with great secrecy to the neighborhood of Chilicothe. But some Indian stragglers had already communicated the alarm; and on the approach of the army, the Indian towns were found already evacuated. The expedition was enabled only to burn the towns and to destroy the Indian crops; after which the soldiers returned to their respective stations in Kentucky.[22]

Not withstanding the constant attacks of the savages, and all the horrors of Indian warfare, the white population continued to pour into Kentucky. But seven years had elapsed since the first attempt to colonize the country, and already, with tempt to colonize the country, and already, with little more than a month’s warning, the infant colonies could send into the field 1000 mounted men. The white population continued to increase so rapidly, that in less than ten years from the date of the battle of the Blue Licks, Kentucky, which had hitherto been a mere county dependent on Virginia, was strong enough to claim admission into the Union, as a separate State. The application was first made in 1790; but the convention of deligates for framing the new State Constitution was able to close its labours only on the first of June, 1792. At this latter date Kentucky was recognized as an independent Commonwealth.[23] She was the first addition to the venerable thirteen, who had gloriously fought the battles of Independence.

This war had come to a triumphant termination in 1782 – the same year that the battle of the Blue Licks was fought. The United States, now freed from all the apprehensions from a foreign foe. Had time to breathe, and to devise measures for the protection of the west from the Indian invasion. In the year 1790, the United States government commissioned General Harmar, with 329 regular troops under his command, to prosecute the Indian war in the northwest. In the west, his army was joined by a much larger body of militia and volunteers; and the expedition marched from Fort Washington – the site of the present city of Cincinnati – on the 30th of Sept. 1790. The Miamis were the first objects of attack.

But General Harmar was unskilled in the tactics of Indian warfare; and he was too confident in his own opinions to listen to the advice of his western subalterns in command. He proceeded against the Indians according to the rules of regular warfare. The savages outgeneralled him, and his expedition turned out a complete failure. After a few month’s campaign, the troops under his command returned to Fort Washington, without having effected anything, except the destruction of the Indian towns and provisions.[24] In this expedition col. Hardin from Kentucky signalized his bravery in many sharp skirmishes with parties of the Indians.

On the failure of General Harmar’s expedition, the veteran, Gen’l. Arthur St. Clair, was appointed to the command of the American army of operations against the Indians. He had fought bravely in the war of the Revolution; but was now old and infirm. So far was he disabled, in fact, that he was carried on the march in a litter. He had under his command about 3000 men, nearly half of whom were regulars. He marched in good order to the Indian towns: but on the memorable 4th of November, 1791, his army was suddenly attacked and defeated, with dreadful slaughter, by the Miamis. His troops were completely routed, and the retreat was a precipitate flight. Many of the soldiers threw away their arms; and the army left in the hands of the Indians their baggage, artillery, and munitions of war. So disastrous a defeat had never yet occurred in the annals of Indian warfare in the west.[25]

So far the Indians had triumphed, even over the regular forces of the United States. They clung with tenacity to the cherished tombs of their fathers; and were prepared to resist to the utmost all attempts of the white man to encroach on their territory. Can any one blame them for thus gallantly defending their own lands and firesides?

A deep gloom overspread the frontier settlements of the west. All were alarmed at the prospect of a dreadful Indian invasion, with its attendant horrors. The terrible war-whoop seemed already to ring in their ears: and the fond mother pressed her infant more warmly to her bosom, as she reflected that perhaps on the morrow its brains might be dashed out by the ruthless savage, and her own head scalped or riven by the knife or tomahawk. The long years of bitter struggle with the Indians had proved, that these terrors were not wholly without foundation.

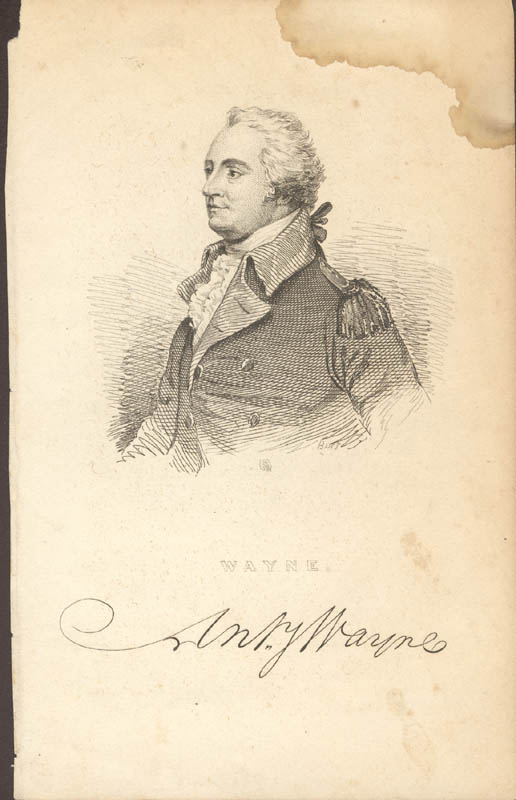

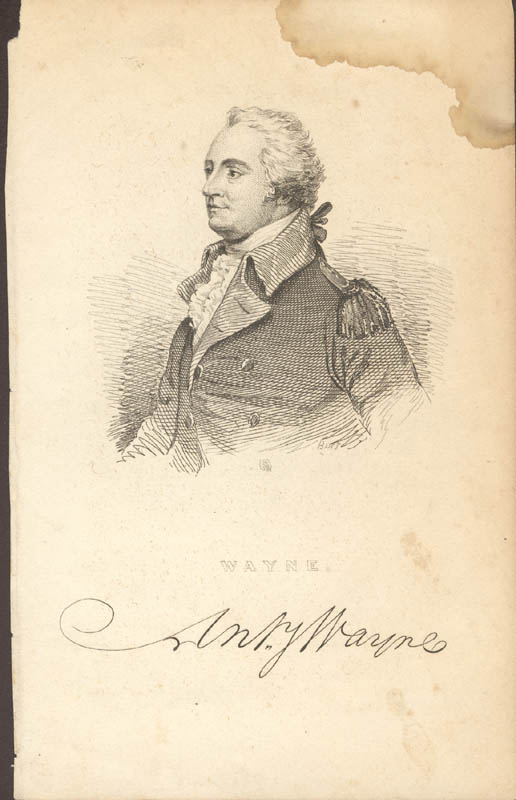

In this emergency, the United States government at length selected a man who was adequate to the undertaking of putting an end to the Indian war, and of thus effectually protecting the western settlements. Gen’l. Anthony Wayne, an officer of the Revolution, combined great coolness of purpose with that impetuosity of bravery, which had already obtained for him the soubriquet of “Mad Anthony.”

This brave and experienced officer marched during the winter of 1793, to the scene of Gen’l. St. Clair’s disastrous defeat. He re-occupied it, and on its site erected a fort, which he called Fort Recovery. In the summer of 1794 he was joined by about 1600 Kentucky volunteers, under Gen’l. Scott: and he then found himself in command of about 3200 troops, one half of whom were regulars. He was unremitting in his labors, to train his army to all the subtle tactics of Indian warfare. He caused them to sleep on their arms; and during the night, he often had them aroused by feigned surprises from the Indians. The troops were thus schooled to the vicissitudes of an Indian campaign.

After having sufficiently trained his men, and engaged in several skirmishes with the savages, he marched his forces to the principal Indian settlements, at the confluence of the Au Glaize and Maumee rivers. Here he attempted a surprise, but without effect, the Indians having already fled. He continued his march to the rapids of Maumee, where, on the 20th of August, 1794, he encountered the whole Indian force. A great and decisive engagement ensued, which, after a short contest, resulted in a complete victory for the Americans. The power of the Indians was broken overwhelmingly, and, as the event proved, for ever.[26]

In the following year, 1795, the great Treaty of Greenville secured a permanent peace between the Indians and the white men, and protected the latter from all fear of further invasion. After this treaty, the Indians made a few more struggles for their territory, which they beheld fast escaping from their hands. They sullenly yielded to their fate, and gradually melted away, before the march of civilization,(!) leaving the graves of their fathers behind them. Thus terminated the Indian border wars of the northwest.

[1] The former in 2 vols. 8vo.; and the latter in 1 vol. 12 mo. The edition of Marshall, to which reference may be made in the sequel, is that of Frankfort, 1824: and of Butler, that of Louisville, 1834.

[2] In the beginning of his first volume (pg. 13, seqq.,) Mr. Marshall indulges in a long and somewhat rhapsodical account of the Indian “annals of Kentucky;” Noah’s flood being the fifth period of his annals!! This is one way to write history!

[3] Thatcher’s “Lives of the Indians,” (P.39) quoted by Butlet, p.2 Edit. Louisville, 1834

[4] Report of Administration of British Colobies – apud. Butler p.3

[5[ Franklin’s Works, vol, iv. p. 271.,

[6] Butler, p. 4

[7] In his reports to Sec’ry. Armstrong, 1814. Amer. State papers.

[8] The present county of Henderson is a portion of this territory.

[9] See Boone’s Narrative, written from his dictation, by John Filson, in 1784: and Butler, p. 18. Seqq.

[10] Butler,pp. 18-19.

[11] For an interesting account of the adventures of the M’Afees, in Kentucky, see Butler, p. 22. Segg. His account is drawn from the M’Afee papers, to which he had access.

[12] Butler, p. 22.

[13] Butler, p. 23-4.

[14] Id. p. 29.

[15] Id. p. 26.

[16] Id. p. 27.

[17] Id. p. 29. seq.

[18] We refer those who may wish to see more on this interesting subject, to the two histories of Kentucky above named.

[19] We have condensed the detailed statement of Butler, derived from the papers of Gen’l. Clark. p. 48. Seqq

[20] For a full account of this remarkable expedition, see Butler, p. 81. seqq.; and for a more detailed and interesting one still, see Judge Law’s able discourse, delivered before the “Vincennes Historical Society,” on the 22nd of Feb. 1839, p. 31. seqq.

[21] See, for a more detailed account of this battle, Butler, p. 125. seqq.

[22] Id. p. 131. seqq.

[23] Id. p. 211.

[24] Butler, p. 191. seqq.

[25] Id. p. 203. seqq.

[26] Butler, p. 235. seqq.