The French Revolution – Virtues of the exiled French Clergy – M. Badin – His early studies – Anecdote – His firm attachment to the faith – He sails for America – Singular coincidence – Anecdote of Bishop Carroll – M. Badin appointed to the missions of Kentucky – Characteristic conversation between him and Bishop Carroll – Departure for Kentucky – Delay in Gallipolis – Arrival – M. Barrieres – M. Badin alone in Kentucky – His troubles – Christian friendship – M. Rivet – M. Badin’s labours in Kentucky – His missionary stations – Teaching Catechism – Morning and evening prayer – His Maxims – Curious anecdote – Hearing confessions – Dancing – Anecdotes – Strange notions respecting Catholic priests – M. Badin’s privations – His disinterested zeal – His dangers and adventures – How to cure the pleurisy – St. Paul

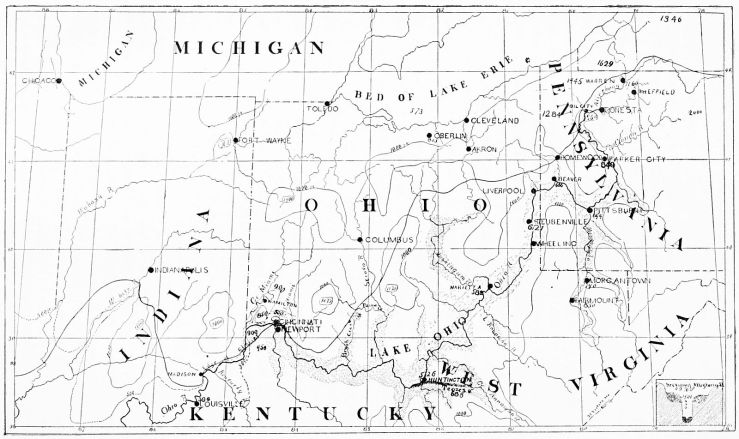

The tide of emigration had continued to set so strongly towards Kentucky, that, on its admission into the Union, in 1792, the population amounted to about 70,000. The Catholic portion of this large population had been, in great measure, deprived of all pastoral succor, since the departure of F. Whelan, in 1790. The next mission to this remote part of the vast Diocess of Baltimore, was commenced under the better auspices, and was destined to be permanent.

The French Revolution had declared a war of extermination against the Catholic religion and clergy. Many of the latter had been driven from France, and compelled to seek shelter in England, Spain, and the United States. The ways of Divine Providence are truly admirable: God often draws the greatest good out of the greatest evil. Many of the most zealous of the French clergy, expelled from their native country, transferred their labours to other lands, and scattered the good seed of the Gospel on the soil of distant regions. Thus persecution, instead of destroying religion, served rather to diffuse it over the world. The exiled clergy of France, in conformity with the advice of our Blessed Lord, when persecuted in one city, fled to another; spreading wherever they went the good odour of Christ. By the fruits which their zeal every where produced, God proclaimed the virtues of his persecuted servants, and confirmed the divinity of a religion, the spirit of which persecution could not quench, or even diminish.

The Catholic Church in the United States is deeply indebted to the zeal of the exiled French clergy; no portion of the American church owes more to them than that of Kentucky. They supplied our infant missions with most of their earliest and most zealous labourers; and they likewise gave to us our first Bishops. There is something in the elasticity and buoyancy of character of the French, which adapts them in a peculiar manner to foreign missions. They have always been the best missionaries among the North American Indians; they can mould their character to suit every circumstance and emergency. They can be at home and cheerful every where. The French clergy who landed on our shores, though many of them had been trained up amidst all the refinements of polished France, could yet submit without a murmur to all the hardships and privations of a mission on the frontiers of civilization, or in the very heart of the wilderness. They could adapt themselves to the climate, and mould themselves to the feelings and habits of a people congenial to them in temperament and character.

One of these French clerical refugees, the Rev. Stephen Theodore Badin, was the man appointed by Divine Providence to succeed the Rev. F. Whelan in the missions of Kentucky, and to become one of the chief religious pioneers of the west. This indefatigable and venerable missionary, still lingering above the horizon of life, celebrated during the last year, the fiftieth anniversary of his arrival in Kentucky, by offering up the Holy Sacrifice in Lexington, the first place at which he had said Mass on his reaching the State. Before we speak of his missionary labours among us, a few incidents of his early life will not, perhaps, be out of place.

M. Badin was born of pious parents, at Orleans, in France, on the 17th of July, 1768. He was the third of fifteen children, and the oldest son. His parents, pleased with the sprightliness of his mind, determined to give him a finished classical education. They accordingly sent him to the College Montagu in Paris, where he remained for three years. He distinguished himself among his fellow students, and soon mastered the ancient classical writers so thoroughly, that he can quote them with facility even to this day. While at this college, he gave frequent evidences of that ready wit for which he was so conspicuous in after life. We will give one little incident of this kind.

His professor of Greek was as remarkable for his penuriousness as he was for his ardent attachment to the ancient Greek authors. He often gave his lessons to youths trembling with cold, though it was his place to have the lecture room warmed at his own expense. One day, he was lecturing on the beauties of Homer, and in his enthusiasm remarked to his shivering hearers, that reading Homer was enough to warm anyone. “It is at least very cheap fuel” – remarked M. Badin, looking significantly at the two little sticks of wood on the fire. All the students smiled, and the professor had a blazing fire in the room the next day.

Having determined to study for the church, he, in the year 1789, entered the flourishing Theological Seminary conducted by the Sulpicians, at Orleans. Here he remained for two years, until the Seminary was dissolved, in 1791. The circumstances which attended its dissolution served to set forth, in the strongest light, the unalterable attachment of M. Badin to the Catholic faith, and that unyielding firmness of purpose, which was a principal feature in his character throughout life. The Bishop of Orleans had unhappily taken the odious constitutional oath; and M. Badin, with the great body of the seminarians, determined that he would not be ordained by such a prelate. Accordingly, early in July, 1791, about a week before the great anniversary of the taking of the Bastile, he and the majority of his companions left the seminary, fearing, also, that on that day they might be involved in difficulties about the oath.

Not being as yet in Holy Orders, he returned to his parents, with whom he remained until the 3rd of November, 1791; at which time he left his father’s house for Bordeaux, where he had determined to embark for America. Here he met with Rev. MM. Flaget and David, whose company he enjoyed on the voyage. Divine Providence thus caused the three men, who were afterwards destined most to signalize their zeal on the missions of Kentucky, to meet together from different parts of France, without any previous concert, and to sail on the same ship for America. After many years of Arduous missionary duty, in different parts of the United States, these same three devoted missionaries met again amidst the waving forests of our State, where two of them are yet living.

These distinguished exiles from France reached Philadelphia on the 26th, and Baltimore on the 28th of March, 1792. They found that another illustrious colony of French priests had already arrived in Baltimore, six months before.[2]

Early on the morning following their arrival in Baltimore, the exiles went to pay their respects to Bishop Carroll. They met him on the way hastening to pay them the first visit; and they apologized to him for the tardiness which had prevented them from visiting him first. Bishop Carroll, smiling and bowing to them, said, with in effable grace and dignity: “it is surely little enough, gentlemen, that I should be the first to visit you, seeing that you have come 1500 leagues to see me.”

M. Badin was ordained priest by Bishop Carroll, in the old cathedral of St. Peter’s, on the 25th of May, 1793. He was the first priest that was ever ordained in the United States. He shortly afterwards went to Georgetown College, to perfect himself in the knowledge of the English. To show the rapid increase of Catholic clergymen in the United States, at that time, we may here mention the fact, that, when F. Whelan was sent to Kentucky, in 1787, there were scarcely twenty in the whole Union; whereas there were twenty-four who attended the first Synod held in Baltimore by Bishop Carroll, in 1791, besides a great number employed on the distant missions.

Bishop John Carroll

The mission of Kentucky still continued in a destitute condition; and Bishop Carroll’s zeal for all portions of his extensive flock was quickened by frequent and urgent applications for a pastor from the Catholics of that distant region. He selected M. Badin for this arduous mission, and soon communicated his wishes to him. M. Badin manifested great reluctance to undertake so difficult a task; he represented his youth – he was but twenty-five years of age – his slight acquaintance with the English language, and his inexperience. He earnestly requested that some one of more mature age, and better qualified, might be appointed. Bishop Carroll listened to his reasons with great meekness; and finally proposed that no decisive step should be taken for nine days, during which both should unite in prayer, and recommend the matter to God, by performing a novena in unison. M. Badin acceded to the proposal, and departed. On the ninth day he returned according to appointment, when the following characteristic conversation took place.

Bishop Carroll: ‘Well, M. Badin, I have prayed, and I continue still in the same mind.”

M. Badin, smiling: “I have also prayed; and I am likewise of the same mind as before. Of what utility, then, has been our nine days’ prayer?”

Bishop Carroll smiled too; and after a pause, resumed with great dignity and sweetness: “I lay no command; but I think it is the will of God that you should go.”

M. Badin instantly answered with great earnestness: “I will go, then,” and he immediately set about making the necessary preparations for the journey.

The event justified Bishop Carroll’s choice. The buoyant elasticity, the persevering zeal, and the indomitable energy of M. Badin’s character, had not escaped his quick eye; and his great forecast and wonderful power of discriminating character, were not, at least in the present instance, at fault. Perhaps, among all the clergy attached to the vast Diocess of Baltimore, at that time, there was not one better suited to the rugged mission of Kentucky, than M. Badin.

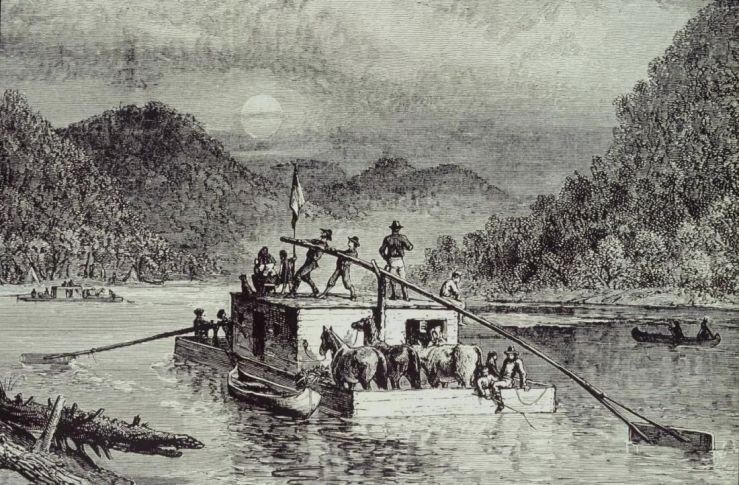

Bishop Carroll, in consideration of M. Badin’s youth, assigned to him as a companion a more aged clergyman – the Rev. M. Barrieres, who was constituted Vicar General in the distant missionary district. The two missionaries left Baltimore on the 6th of September, 1793, and travelled, like the Apostles, on foot to Pittsburgh, over bad roads and a rugged wilderness country. On the 3rd of November, they embarked on a flat boat, which was descending the Ohio, in company with six others. These boats were all well armed, for fear of an attack from the Indians. About that time, however, Gen’l. Wayne was preparing his great expedition against them; and they had enough to do to defend their own wigwams, without prowling about near the frontier settlements.

The boats were seven days in going down to Gallipolis; and between this place and Pittsburgh, the travellers saw but two small towns – Wheeling and Marietta. The two priests remained for three days at Gallipolis, the inhabitants of which place were French Catholics, who had been long without a pastor. They heartily welcomed the missionaries, who, during their brief stay, sang High Mass in the garrison, and baptized forty children. The good French colonists were delighted; and shed tears on their departure. They were but a remnant of a large French colony of about 7000, who had emigrated to America four or five years previously. A French land company had purchased for them a large territory on the Scioto river; but the title to these lands proved defective; the colonists were defrauded, and many of them returned in disgust to France, bitterly inveighing against Yankee shrewdness in bargaining.

The two missionaries landed at Limestone, or Maysville, where there were at that time about twenty families. They proceeded on foot to Lexington, a distance of about 65 miles. They passed the first night in an open mill, six miles from Limestone, lodging on the mill-bags, without any covering, during a cold night, late in November. On the next day, they passed the battleground of Blue Licks, where M. Barrieres picked up a skull of one of those who had fallen there eleven years before. He carried it with him, and retained it, as a relic of the disastrous battle, and as a memento of death. On the first Sunday of Advent, M. Badin said Mass, for the first time in Kentucky, at Lexington, in the house of Dennis M’Carthy, an Irish Catholic, who acted as clerk in the commercial house of Col. Moyland, brother of the then Bishop of Cork.

The missionaries had with them but one chalice; and after having offered up the Holy Sacrifice, M. Badin travelled sixteen miles, to the Catholic settlement in Scott County, where M. Barrieres said Mass on the same day. Preparations were then in progress to erect in this place a frame church. M. Badin remained in Scott county for about eighteen months, occasionally visiting the other Catholic settlements in Kentucky; M. Barrieres proceeded immediately to take charge of the Catholic families in the vicinity of Bardstown.

The difficulties of the times, and the rude state of society in the infant colonies, soon determined M. Barrieres to leave the country. His habits had already been formed, and he thought that he could not adapt himself to the new state of things in the wilderness. Accordingly, about four months after his arrival in Kentucky, he left the State. In April, 1794, he departed from Louisville, in a pirogue[3] for New Orleans, which, with all Louisiana and Missouri, was then in possession of the Spaniards.

The Spanish government was at that time apprehending an attack on Louisiana from the French Republic; and M. Barrieres, being a Frenchman, was arrested and detained for some time at New Madrid. He immediately wrote to Baron Carandolet, the Spanish Governor of Louisiana, representing the objects of his visit; and the Baron soon liberated him, and permitted him to proceed without further molestation, to New Orleans. Shortly after his arrival in this city, he went to Attakapas, where he labored zealously in the missions for nearly twenty years. In 1814, he sailed for Bordeaux, where he died eight days after his arrival. About twenty-three years before, he had escaped from a prison of this city, and from the death which probably awaited him at the hands of the French Jacobins; and he had sailed from this port to America; and now he returned to the same place to breathe his last.

M. Badin was now left alone in the heart of the wilderness. Keenly as he felt the desolation of heart which this state of isolation brought with it, he yet reposed his whole trust in God, who abundantly consoled him in all his tribulations. He remained alone for nearly three years, and was at one time twenty-one months without an opportunity of going to confession. He had to form the new congregations, to erect churches as suitable places, and to attend to the spiritual wants of the Catholic settlements scattered over Kentucky; and he had to do all this alone, and without any advice or assistance. Well might he exclaim; “Oh! How much anguish of heart, how many sighs, and how many tears, grow out of a condition so desolate!”[4] Still he was not cast down, notwithstanding all his perplexities.

His mind was also soothed by the cheering voice of friendship. The nearest Catholic priest was M. Rivet, who was stationed at Post Vincennes in 1795, shortly after the departure from that station of the illustrious missionary pioneer, the Rev. M. Flaget. In France, he had been professor of Rhetoric in the College of Limoges: and he still continued to write Latin poetry with case and elegance. He occasionally sent his Latin poems to M. Badin, who also, as we shall see, excelled in this species of composition. When the French Revolution burst over Europe, M. Rivet took refuge in Spain, where the Archbishop of Cordova made him his Vicar General, for the benefit of the numerous French refugees who had taken shelter beyond the Pirrenees.

He and M. Badin mutually consoled each other, by carrying on as brisk a correspondence as the difficulties of the times would permit. There were then, however, no post offices in the west; and the frowning wilderness which interposed between the two friends rendered the exchange of letters extremely difficult; and wholly precluded the possibility of their visiting each other; even if this had been permitted by the onerous duties with which each was charged. M. Rivet had discovered at Vincennes a precious document of the old Jesuit missions among the Indians of the northwest. It consisted of two large folio volumes in manuscript, containing the Mass, with musical notes, and explanations of it, together with catechetical instructions, in the Indian language. This document has probably since disappeared.

When M. Badin first came to Kentucky, he estimated the number of Catholic familes in the state at three hundred. These were much scattered; and the number was constantly on the increase, especially after Wayne’s victory in 1794, and the treaty of Greenville in the following year. There was then but one Catholic in Bardstown – Mr. A. Sanders, to whose liberality and generous hospitality the clergy of the early church in Kentucky were so much indebted.

He found Catholics suffering greatly from previous neglect, and in a wretched state of discipline. Left alone, with this extensive charge, he had to exert himself to the utmost, and, as it were, to multiply himself, in order to be able to meet every spiritual want of his numerous flock. As the Catholics were then almost wholly without churches or chapels, as he was under the necessity of establishing stations at suitable points, in private houses. These stations extended from Madison to Hardin county – a distance of more than a hundred and twenty miles; and to visit them all with regularity, he was compelled almost to live on horseback. He estimates that, during his sojourn in Kentucky, he must have rode on horseback at least 100,000 miles. Often was he exhausted with his labours, and weighed down with the “solicitude of all the churches.”

His chief stations during this time were those at Lexington, in Scott county, in Madison county, in Mercer county – where there were then about ten families – at Holy Cross, at Bardstown, on Cartwright’s Creek – two miles from the present church of St. Rose – on Hardin’s Creek, on the Rolling Fork, in Hardin county, and at Poplar Neck on the Beech Fork.

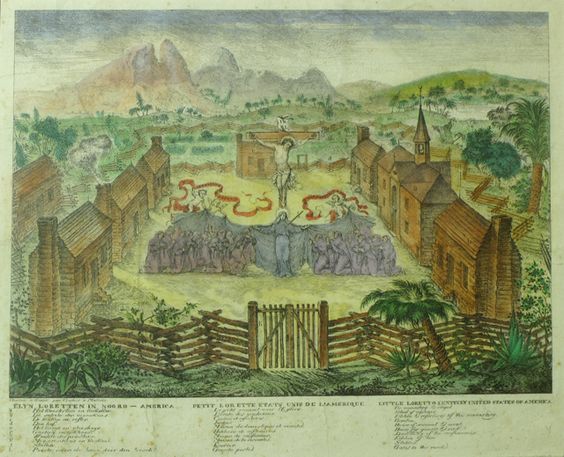

In all those places, except Madison and Mercer counties,[5] there are now fine brick churches; but at the period of which we are speaking, there was not one of any kind, except a miserable log chapel, on the site of the present church of Holy Cross; and this had been erected at the instance of M. De Rohan, before the arrival of M. Badin in Kentucky. This temporary hut was covered with clapboards, and was unprovided with glass in the windows. A slab of wood roughly hewed, served for an altar. Such was the first Catholic church in Kentucky! As it was situated near the centre off the Catholic settlements, M. Badin soon took up his residence near it; and it then became the central point of his mission, and the alma mater of Catholic churches in Kentucky. He subsequently erected a temporary chapel at his own residence, three miles from Holy Cross; this he called St. Stephen’s, after his patron Saint.

M. Badin was indefatigable in his efforts to awake piety, and to restore a proper discipline among his flock. He insisted particularly on having servants and children taught the catechism. At every station he had regular catechists, whose duty it was to teach them the elements of the faith. He displayed on all occasions particular zeal in the instructions off poor servants off colour. Whenever he visited a Catholic family, it was his invariable custom to have public prayers, followed by catechetical instructions. He every where inculcated by word and example the pious practice of having morning and evening prayer in families. He was in the habit of repeating to children, in his usual emphatic and pointed manner, the following maxims; “My children, mind this; no morning prayer, no breakfast; no evening prayer, no supper;” and “my children, be good, and you will never be sorry for it.”

His zeal for promoting the regular practice of morning and evening prayers, occasionally betrayed him into some eccentricities. Once, a man travelling to the Green river country, called at his residence at St. Stephen’s, at a late hour in the evening, requesting permission to stay during the night. M. Badin cheerfully granted the request, telling him at the same time, that he was a Catholic priest, and could charge nothing for his hospitality. The man looked a little shy, but thanked him for his kindness. When, after supper, he was about to retire to rest, M. Badin asked him, whether he had said his night prayers? The man looked blank, and answered in the negative. “Well,” rejoined M. Badin, “I have already said my prayers, but I will cheerfully say them again to accommodate you, and to bear you company.” Then he immediately fell on his knees, the man following his example, and said aloud the usual prayers. As he was lighting his guest to his room, he told him, “that he might die before morning, and that he should never retire to rest without preparing himself for death.” On the next morning, M. Badin went to awake the stranger, but he had, it seems, said prayers enough already, and had escaped before the dawn of day.

On reaching a station, M. Badin would generally hear confessions till about one o’clock. Meantime, the people recited the Rosary at intervals, and the boys, girls, and servants, were taught catechism by the regular catechists. Hearing confessions was the most burdensome duty he had to discharge; and he was fully aware of its deep and awful responsibility. He spared no labour nor pains to impart full instructions to his penitents, who thronged his confessional from an early hour. So great, in fact, was their number, that he found it expedient to distribute among them tickets, fixing the order in which they should approach the holy tribunal, according to priority of arrival at the church. He was a thorough tactician, and was inflexible in maintaining this order. Frequently, persons would be obliged to make several attempts before they could succeed in going to confession.

He was always an implacable enemy of dancing, which, in the rude state of society at that early period, was often attended with great disorders. The following amusing anecdotes will illustrate the manner in which he warned against the practice.

Some time in the year 1795, or 1796, the Catholics on Pottinger’s Creek got up a dancing school and employed an Irish Catholic as a dancing-master. In his regular visit to the neighbourhood, M. Badin repaired as usual to the station on Saturday evening, to hear confessions and to teach catechism to the children. He found very few in attendance, and soon learned that they were all gone to the dancing-school, at a neighbouring school-house. He immediately went thither himself, and his appearance disturbed, in no slight degree, the proceedings of the merry assemblage: “My children,” said he, smiling, as he stood in the middle of the room, “it is all very well: but where the children are, there the pastor must attend.” He caused them all to sit down, and he gave them a long lesson in their catechism. On the following morning, he said Mass for them in the same apartment, and caused the dancing-master himself to attend.

He sometimes arrived unexpectedly at a house, in the evening, while dancing was going on, glided into the room before any one perceived it, and told them smiling, “that it was time for night prayers.” The action was suited to the word, and most of the merry dancers generally effected their escape before the close of the evening devotions. He managed all this with so much tact and good humour, that the people acquainted with his eccentricity, and respecting his zeal, were not usually offended at his conduct.

It is indeed strange, what ideas many Protestants then had of a Catholic Priest. They viewed him as something singular and unearthly, wholly different from any other mortal. Often, when M. Badin was travelling, he observed people peeping timidly at him from behind the corners of houses: and once, in particular, when it was rumoured through a neighbourhood, that the priest was coming to a certain house, a party concealed themselves in the woods near the road, in order to have a peep at him as he was passing. They were afterwards heard to wonder that the priest was like any other man, and that he was no great show after all! And yet those people lived in an age of “open Bibles,” and of boasted enlightenment! And yet the preachers, who are mainly chargeable with keeping up this absurd prejudice, have still the assurance to charge the Catholic priests with keeping the people in ignorance!! This bigotry has indeed abated, but it is not yet wholly extinct.

In his solitary and forlorn condition, M. Badin was wholly deprived of the luxuries, and often suffered for the necessaries of life. His clothing was made of cloth manufactured in the country:[6] and his food, besides being often scanty enough, was of the coarsest kind. For several years, he was often compelled to grind his own corn on the hand-mill. He asked for his support the hundredth bushel of grain that was raised by the members of his congregation; but for various reasons he did not usually receive the thousandth. Once, he was for many days without bread, at his own residence of St. Stephen’s; until the good Mr. Sanders, who became accidently apprised of the fact, sent him the necessary supply.

The following incident will serve to show how disinterested was his zeal, in the midst of all these privations. In the year 1796, when his sufferings and hardships were the greatest, he received a letter from the Spanish Governor of St. Genevieve, earnestly pressing him to leave Kentucky, and come to reside in St. Genevieve, where he was offered and annual salary of $500, besides valuable perquisites. The situation was easy and inviting, and the offer was tempting. M. Badin, in fact, viewed the whole matter in the light of an evil temptation to abandon the field of labour which Divine Providence had assigned him; and he accordingly threw the Governor’s letter into the fire, and did not even return any answer. His motto was: follow Providence.

This chapter would swell to an unwarrantable length, should we attempt to describe all the dangers through which M. Badin passed, or to relate a tenth part of the strange adventures with which he met. The subject will probably come up again in the sequel. We will here state, that he was often called to a distance of fifty, and even eighty miles, to visit the sick,[7] on which occasions he had to strain every nerve, and to ride day and night, in order to be able to meet his other pressing engagements. He made it an invariable rule never to miss an appointment, no matter what obstacles interposed.

He often missed his way, and was compelled to pass the night in the woods, where he kindled a fire, by the light of which he said his office. On one of these occasions, a heavy rain sset in and continued during the whole night: the leaves were so wet, that his companion had to climb some neighbouring trees, in order to collect dry fuel for lighting the fire, an operation which consumed three hours. Yet they passed the night merrily, singing and praying alternately; and at break of day had the satisfaction to find that they were but five feet from the road.

Once, he lost his hat in the night, and being unable to find it in the darkness, was compelled to ride many miles bareheaded, to the distant station which he was on his way to visit. On another occasion, while about to cross Salt river, near the mouth of Ashe’s creek, his horse missed his footing in the darkness, and rolled down the elevated cliffs with his rider. M. Badin found himself in a deep fish-pot, with one foot in the stirrup and the other immersed in the water. The horse, usually spirited and restive, stood perfectly quiet, and the rider was unhurt. He had the Blessed Sacrament with him, and he returned thanks to God for his preservation from a danger so imminent.

In short, he passed through almost as many hardships and dangers as St. Paul so graphically describes in his Second Epistle to the Corinthians.[8] Yet he was not discouraged, nor was his health impaired. His strength seemed even to increase with the hardships he had to endure. And he was consoled by the abundant fruits with which God was pleased to bless his ministry. Of these we purpose to treat more at length in a subsequent chapter.

[1] For almost all the facts contained in this chapter, we are indebted to the Very Rev. S. T. Badin, whose tenacious memory of facts and dates is really astonishing, considering his advanced age and the hardships through which he has passed. Like most old persons, he remembers events long passed much better than those of more recent occurrence.

[2] On the breaking up of the seminary at Orleans, M. Chicoipneau, the superior, had also proposed to emigrate to America; but some cause detained him in France.

[3[ A large species of canoe, then much used on the Ohio and Mississippi.

[4] From a brief statement of the missions of Kentucky drawn up by M. Badin, while in France in the year 1822, and published in the “Annales de la Propagation de la Foy,” for 1823, No. 2. This statement is very condensed, but admirably written.

[5] The Catholics have since, in a great measure, removed from both of these counties; and, in consequence, the brick church formerly erected in Danville, Mercer county, has been disposed of.

[6] Judge Broadanax used to compliment him for his patriotism, in thus encouraging domestic manufacturers: but there was evidently more of a necessity than of virtue in the matter.

[7] After one of these long rides, he found the sick man sitting on a stool, eating hard boiled eggs, to cure the pleurisy.

[8] Chap. xi. 26 seqq. “In journeys often, in perils of rivers, in peril of robbers, in perils from my own nation, in perils from the Gentiles, in perils in the city, in perils in the wilderness,…..in labour and painfulness, in watchings often, in hunger and thirst, in many fastings, in cold and nakedness,” &c.