On this page of my blog I want to share some of the history of the Catholic Church in Kentucky and the men and women who kept the flame of the faith ignited in the wilderness!

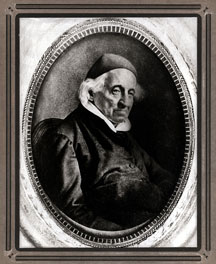

The Reverend Mister Stephen Theodore Badin

Stephen Theodore Badin spent the majority of his missionary years and labors in Kentucky, yet his greatest monuments are elsewhere. Indiana claims his grave, at Notre Dame and Ohio his death bed but Kentucky claims his best work.

Stephen Theodore Badin was born in Orleans France July 17, 1768, the 3rd of 15 children and the first male in the family. As was the norm for that time, he was carried to the church at 12 hours old to be baptized.

He must have been from a well to do family and parents of solid faith, because they were able to give all their children a good education, and religious training that led two of them to the priesthood.

1789 – the start of the French Revolution and the year that Badin entered the seminary at Orleans under the direction of the Sulpicians. Two years later the Revolution reached Orleans and the seminary was closed. Sadly, the Bishop of Orleans had taken the oath of allegiance to the revolutionary government, and this shut off all hope of any young seminarian to be ordained to the Catholic Church – staying they would have to become members of the Constitutional Church. All this made Badin determined to go to America where he could exercise a ministry denied him at home.

Our hero, along with the superior of the late seminary at Orleans, went to Bordeaux and there they met two professors of the Sulpician seminary at Angers – that seminary had met the same fate as the Orleans seminary. The two were the Reverend Misters Flaget and David – both of whom will be closely associated in Badin’s life.

January 1792 the three sailed for America. They reached Philadelphia on March 28th and immediately went to Baltimore (immediately is the 2 – 3 days travel) where they were heartily greeted by Bishop Carroll, who was expecting them. The Sulpicians attached themselves to their community in Baltimore and Badin entered the seminary under them to finish his studies for the priesthood.

Badin could have been in minor orders when he arrived at America, acolyte, lector, porter, but he had not received any major orders. Some historians waver on this but from a letter written by Badin, himself, to Bishop Purcell of Cincinnati, and I will mention, written in Huntington Indiana on September 22, 1834.

“The date of this letter reminds me that this day forty-two years ago the first Bishop of Baltimore ordained the first subdeacon of his diocese, and gave the tonsure and minor orders to three or four ordinandi. . . . To serve you it would be gratifying to me to extend my labors to the N. W. of your diocese, but the above date of my ordination has already informed you that I am more than sixty-six years of age, etc.”

This was probably the first ordination of any kind in the United States, and the next must’ve been when he received the diaconate – but alas that date seems to be lost. We do know he was ordained to the priesthood on May 25, 1793 and thus the title, which he often liked to use, of Proto-priest of the United States.

Bishop Carroll’s jurisdiction extended over the whole of the United States and last week we heard of the sad state of the Catholics in the wilderness of Kentucky, and the lack of clergy – deserved or not – in the area. Bishop Carroll was receiving frequent and urgent requests for a pastor in Kentucky and he was determined to meet their needs.

Soon he selected Reverend Mister Badin for this mission of which Badin showed and voiced a great reluctance to undertake. He spoke of his youth, he was just 25 years old, his lack of profiency of the English language, and his inexperience. He suggested the Bishop pick someone more mature.

Bishop Carroll listened to all the Reverend Mister’s reasons and proposed that no decisive step be taken for nine days. During those nine days they should both unite in a novena, and recommend the matter to God. Badin agreed and left the good bishop. On the 9th day he returned and the following conversation took place:

Bishop Carroll. “Well, Mr. Badin, I have prayed, and I continue still in the same mind.”

Mr. Badin, smiling: “I have also prayed; and I am likewise of the same mind as before. Of what utility, then, has been our nine days’ prayer?”

Bishop Carroll smiled too; and after a pause, resumed with great dignity and sweetness: “I lay no command; but I think it is the will of God that you should go.”

Badin instantly answered with great earnestness: “I will go, then,” and he immediately set about making the necessary preparations for the journey.

The event justified Bishop Carroll’s choice. The buoyant elasticity, the persevering zeal, and the indomitable energy of Mr. Badin’s character, had not escaped his quick eye; and his great forecast and wonderful power of discriminating character, were not, at least in the present instance, at fault. Perhaps, among all the clergy attached to the vast Diocese of Baltimore, at that time, there was not one better suited to the rugged mission of Kentucky, than Mr. Badin.

Bishop Carroll, in consideration of Mr. Badin’s youth, assigned to him as a companion a more aged clergyman—the Rev. Mr. Barrieres, who was constituted Vicar General in the distant missionary district.

The Reverend Mister Badin returned to Paris in 1821 to seek support for the mission field he had worked for so many years. In a pamphlet he wrote:

“A score of poor Catholic families, descendents of the English colonists of Maryland, established themselves in Kentucky in 1785, because they could then procure good land for almost nothing. Their number soon increased, and Father Whelan, an Irish Franciscan, was sent to them in 1788. Owing to the war with the savages, which lasted until 1795, this missionary, two of his successors and the colonists were obliged to pass through a hostile country to arrive at their destination, where also they were often exposed to imminent danger of their lives. Besides being far from any other priest, he had to struggle against poverty and want, against false religions and the widespread prejudices concerning the supposed idolatry of the Catholics, etc. At the end of two years and a half Father Whelan finally abandoned a position he found so difficult to hold, and he had not the satisfaction of seeing a single chapel rise in his entire mission.

“It was impossible at this time to find another missionary to succeed him, and the faithful suffered much, because they were as a flock without a shepherd (Zach. x). Finally, in 1793, the priesthood was conferred for the first time in this part of the world, where the Catholics had been groaning but a little while before under the penal laws of England, and the priest first ordained by the illustrious Mr. Carroll, the first Bishop of Baltimore, was Mr. Badin of Orleans, and shortly afterward Bishop Carroll sent him to Kentucky.

“In addition to the difficulties which confronted his predecessor, this young ecclesiastic found new ones in his own inexperience, his imperfect knowledge of English, and his ignorance of the manners and customs of the country. One can easily imagine how painful must have been the situation of a novice thus isolated and deprived of a guide in a ministry whose weight, as the Fathers of the Church tell us, would be formidable to the very angels It is true that he left Baltimore with another priest, who was invested with the powers of vicar-general, but this priest soon became dissatisfied with the rustic manners of the settlers and with their mode of life, and four months had scarcely passed before he left the settlements and went to New Orleans: Mr. Badin, to his regret, then found himself charged with the entire mission, and for several years was alone in the care of it, although, especially after peace was concluded with the savages, it continued to grow, through the influx of Catholics who came from Marvland and other countries”

Nothing but necessity could have induced Bishop Carroll to send a priest of only a few months standing to such a mission as Kentucky and nothing but the will of God could have kept him there.

The Reverend Mister Badin set out on September 6th, with Father Barriers, an older priest assigned as Vicar-General for the area of Kentucky, on foot from Baltimore to Pittsburgh. They arrived without incident and on November 3rd embarked on a flatboat manned by six well armed men prepared to meet any attack. They were not attacked as the Indians were busy gathering their forces in anticipation of a war with General Wayne, who was preparing for an expedition against them.

The boats were seven days going down to Gallipolis where the 2 priests remained for 3 days. The settlers here were French Catholics who had long been without a pastor. They heartily welcomed the missionaries who during their brief stay, sang High Mass at the garrison and baptized forty children. These good French colonists were delighted and shed tears upon the departure of the priests.

The two priests landed at Limestone, Maysville, where there were about 20 families at that time. They proceeded on foot to Lexington – about 65 miles. The first night was spent in an open mill, six miles from Limestone, sleeping on mill-bags, without any covering.

The next day they passed the battle ground of the Blue Licks, where Reverend Mister Barriers picked up the skull of one of those who lost his life there eleven years earlier. He carried it with him as a relic of the disastrous battle and as a memento of death.

On the first Sunday of Advent Father Badin said Mass, for his first time in Kentucky, at Lexington, in the house of Dennis McCarthy, an Irish Catholic.

The missionaries only had with them one chalice, so after offering the Mass in Lexington, the Reverend Misters Badin and Barriers travelled the sixteen miles to the Catholic settlement in Scott County where Father Barriers said Mass on the same day.

The settlers at Scott County already had preparations in progress to erect a frame church. Badin remained at Scott county for about 18 months and Barriers went on to Bardstown.

The Reverend Mister Barriers couldn’t take it. He could not adapt to the wilderness and after four months he left the state.

Father Badin, at 25 years old and less than a year ordained to the priesthood, found himself alone in the heart of the wilderness. Badin’s trust in God – in Divine Providence – is what consoled him during these times of tribulation.

He remained alone for nearly three years, and at one point went 21 months without an opportunity for confession. He went about forming new congregations, erecting churches at suitable places and attending to spiritual wants and needs of the Catholic settlements scattered all over Kentucky, and all this he had to do alone, without the advice or assistance of a mentor or friend.

Badin then moved to Washington county and made his home in the center of his missionary district. On Pottinger’s Creek he found a log chapel, built some time before by Father De Rohan – the wandering priest we spoke of last week – the first and only semblance of a Catholic Church in all of Kentucky. Father Badin secured a plot of land a few miles from this chapel and built a small cabin of two rooms and a small chapel. This was first called “Priestland” but later he named it Saint Stephen’s in honor of his patron saint. This is now where the Motherhouse of the Sisters of Loretto resides.

At this time the Reverend Mister Badin estimated the Catholics in Kentucky at about 300 families. The majority resided in Nelson and Washington counties, with smaller clusters of Catholics as far east as Lexington and west as Hardin county. After General Wayne’s victory over the Indians in 1794, the number was rapidly increasing and becoming more scattered throughout the state.

Before he got much help on the mission field, his charges extended from from Vincennes, in Indiana, to Knoxville in Tennessee, and from Lexington to the Mississippi River, and he managed to visit all of them!

We can only do a brief summary of his work here, and of the conditions under which he labored. He found the Catholics suffering from long neglect, and without order or the habit of pious exercises. He established regular mission stations in private houses in all the groups of settlers, and sought out individual families between times. He was virtually forced to live in the saddle, and every day was marked by ”holding Church” in one or another of the settlements. Everywhere he went he strove to awaken piety, and restore a proper spirit of discipline among his flock. He appointed catechists at every station, whose duty it was to teach the elements of the Faith to the ignorant, and he insisted upon the children learning the catechism by heart. Servants and slaves were also instructed, and grown up persons were not immune from his searching examinations upon the essentials of their religion. Family prayers, night and morning, were universally inaugurated, and “Middle-day Prayers” on Sundays, at which all should attend. “My children,” he would say, “no morning prayer, no breakfast; no evening prayer, no supper. Be good, and you will never be sorry for it.”

He was the implacable enemy of dancing and other dissipating amusements, and sometimes, when arriving at a settlement and finding a dance in progress, he went to the house, and entering said with a sly smile to the startled throng: “My children, it is all very well, but where the children are there the father must be; and where the flock is there the shepherd must attend.” Then he would make them all sit down, and he would give them a long lesson in catechism, and end all with night prayers.

Adventures he had of all kinds-getting lost in the woods, getting wet in storms and rivers, sleeping in the forests with wild beasts prowling around, and not least, refuting in public and in private the multitudinous accusations, slanders and absurdities of the preachers in regard to Catholic teaching and practice.

If Father Badin were not a tough and wiry Frenchman he would have worn himself out, and as it was, his death was reported several times. Yet he voluntarily continued in all these labors which brought no remuneration but the satisfaction of spirit at seeing God served and souls saved in this wilderness. For his support he asked from the people but one bushel in a hundred of their produce, and they gave him less than one in a thousand, and yet he had to provide for almost all the cash expenditure in the building of their churches. If he had less of the apostolic spirit he might have escaped most of his privations and sacrifices, for, in 1796, (remember he is just 28 years old at this time) when his sufferings and hardships were greatest, he received a letter from the Spanish Governor at St. Genevieve, earnestly pressing him to come there to live, and offering him an annual salary of $500 and valuable perquisites. We are told that he threw the letter into the fire and did not even return an answer.

Young Father Badin was by himself on this mission field until 1797 when Father Fournier came to help and in 1799 Fathers Salmon and Thayer also came. Father Salmon was killed in an accident (more next week on that), Father Thayer, a convert, just couldn’t adapt to this wilderness and Father Fournier met his death in 1803 from a ruptured blood vessel through over exertion in lifting logs for the building of his house.

Once again, Badin found himself alone until 1805 when the Trappists came, four Dominicans and one missionary priest – Father Charles Nerinckx – who quickly became one of my favorites!

The Trappists did little or no missionary work and soon moved on. The Dominicans established their convent at Saint Rose, and became very active on the mission field. Still, the majority of the work remained on the shoulders of Father Badin and his new colleague and friend Charles Nerinckx.

Up to this time Badin had been successful in building six churches in the principal settlements. One in Scott County, one at his home, one on Pottinger’s Creek, one on Hardin’s Creek one on Cartwright’s Creek and one in Bardstown. At the time they had no religious titles but since are known as St. Francis, St. Stephen’s, Holy Cross, St. Charles. St. Ann’s, and St. Joseph’s.

He seemed to be very talented at acquiring land and had secured several tracts where churches were planned for in the future. On one of those tracts, near his house, he began building a large house for young women who were to be the first members of a new religious order of teachers. The structure was destroyed by fire in 1808 and Badin had to wait four more years before he saw the fulfillment of his desire to provide Christian education for children when Nerinckx founded a sisterhood – the Sisters of Loretto at the Foot of the Cross.

The desire for a bishop to lead this vast mission field and to confer with was always a desire of Badin’s but really found expression in the people too in 1806.

Bishop Carroll thought of him, and the people of Kentucky thought of him, but it is not probable that he himself entertained any serious desire for the position. Bishop Carroll of Baltimore favored his appointment, but the people of Kentucky, at least a large portion of them, were opposed to it. In his dealings with the people, and especially in his efforts to repress evil, he was rather severe, and was not what might be termed a popular priest. No doubt some severity was

necessary, and discipline was more severe then than now, but human nature was the same, and resented repression. Pretexts were seized upon by some of the dissatisfied, and a storm was raised against Father Badin in certain quarters, ostensibly on account of his severity, arbitrariness and imperiousness. He had urged measures of reform and conduct that were not pleasing to those needing them, and hence the storm.

So in 1807 Father Badin set out for Baltimore. Badin’s goal was to represent to Bishop Carroll the importance of having a bishop appointed for Kentucky.

And I share a tid-bit from the Sketches book……….

We must briefly relate a little incident which occurred on this journey. He seldom omitted any opportunity of preaching, or of doing good. When he had reached Brownsville, Pennsylvania, he was invited to preach; and the Methodist meeting-house was politely tendered to him for this purpose. A large concourse of people were in attendance, anxiously desiring to see the priest, and to hear what he had to say. M. Badin ascended the pulpit, and having made the sign of the cross, and said some preliminary prayers, he began his discourse, with a good humoured smile, somewhat in this characteristic way: “My dear brethren you have been in the habit of hearing the Gospel incorrectly preached, and of hearing the doctrines of the Holy Catholic Church misrepresented from this place: I mean to tell you the truth, and the whole truth.” He then clearly stated the Catholic doctrine, furnishing scriptural proofs as he advanced, and answering the most common objections. He proved that Catholics, far from rejecting the Bible, were really its best friends and truest expounders; and that, but for the Catholic church, Protestants would not even have the Bible.

His discourse made a deep and lasting impression. Among his hearers was a Major Noble, a man of considerable talent and standing in that vicinity. After the sermon, he invited M. Badin to his house; and after having conversed with him at length on the doctrines and practices of Catholicity, he determined to become himself a member of the church. M. Badin had the consolation to baptize him and to offer up the Holy Sacrifice in his house. Mrs. Noble was still deeply prejudiced against the Catholic church; but she became uneasy in mind, and after having prayed, and read attentively some Catholic works which M. Badin left with the family, she too resolved to become a Catholic. On his return from Baltimore, M. Badin had the great happiness to baptize her, and all the other members of the family.

Badin wasted no time relating to Bishop Carroll the needs of the Catholics in his mission field. Bishop Carroll wanted Father Badin, and would probably have had him appointed if Father Badin himself had not gone to Baltimore in 1807 and recommended Father Flaget, with whom he had come to America.. Father Badin’s name was put on the list, but the special recommendations were for Father Flaget. We have seen where this prelate told Father Badin: “Without you, they would never have thought of making me a bishop.”

We can delve more into the first Bishop in Kentucky at a later date but I do want to share the preparations and welcome made for the new bishop.

The new bishop’s party sailed by flatboat and arrived in Louisville on the 4th of June, 1811 where they were met by Father Nerinckx. He escorted them to Bardstown and to Saint Stephen’s, the residence of Father Badin. They reached Bardstown on the 9th and Saint Stephen’s on the 11th. Here they were welcomed by a large assembly of people gathered to see their new bishop for the first time. Also gathered in this place were the Reverend Misters Badin, Fenwick, Wilson, Tuite, Nerinckx, O’Flynn, David and a Canadian priest who accompanied them from Pittsburgh. Eight priests, more than had ever been seen together in Kentucky!

We will end with Reverend Mister Badin’s recount of that day…………..

“The Bishop there (at St. Stephen’s) found the faithful kneeling on the grass, and singing canticles in English: the country women were nearly all dressed in white, and many of them were still fasting, though it was then four o’clock in the evening; they having indulged the hope to be able on that day to assist at his Mass, and to receive the holy Communion from his hands. An altar had been prepared at the entrance of the first court, under a bower composed of four small trees which overshadowed it with their foliage. Here the Bishop put on his pontifical robes. After the aspersion of the holy water, he was conducted to the chapel in procession, with the singing of the Litany of the Blessed Virgin; and the whole function closed with the prayers and ceremonies prescribed for the occasion in the Roman Pontifical.”

The statistics of the new diocese at that time were as follows, there were more than a thousand Catholic families, including many who had been received into the church by the earlier Catholic missionaries. The Catholic population did not probably exceed, even if it reached, 6000. There were six priests, besides the Vicar General, who administered the Sacraments to more than thirty different congregations or stations, about ten of which only had churches or chapels erected. The names of the churches then in Kentucky, are as follows : Holy Cross, St. Stephen’s, Holy Mary’s St. Charles, St. Ann, St. Rose, St. Patrick, St. Francis, St. Christopher, and St. Joseph. Besides these, the following were in progress of erection: St. Louis’, St. Michael’s, St. Clare’s, St. Benedict’s, St. Peter’s, and St. John’s, There was also one convent of Dominicans, and several residences for the clergy. Finally, there were six plantations belonging to the church, besides several bodies of uncultivated lands.

In the beginning of the year 1853 his health began to fail more rapidly, and it was evident that the end was not far off. On April 19th of that year the Archbishop and priests of the Cathedral were gathered around his bed, a terrific thunderstorm was passing over the city, but the storm passed, a stillness reigned outside, brightness came into the sky again, they looked at the quiet figure on the couch-his soul had just passed away. The Proto-priest of the United States had gone to join the Proto-bishop who had ordained him, and the other great missionaries with whom he had labored preparing the ground and planting the seed of the Church of God in the most promising field of modern times. His remains were placed beside those of Bishop Fenwick under the Cathedral, as he once said they might be, and his wish thus expressed may explain why Kentucky never laid claim to them. Ohio profited by Kentucky’s sacrifice. They who knew him appreciated the gift, and it is said that Archbishop Elder of Cincinnati, for his private devotions in the Cathedral, always selected a certain obscure corner in the sanctuary, and when asked why he did so, replied that it was because under that spot lay the remains of Father Badin.

But” the older generation passed away and with it many of its memories, so that, in 1904, when the Fathers of the Holy Cross asked that his remains be transferred to their institution at Notre Dame, Indiana, their request was granted. On the .

spot where he built his log chapel at that place when he was a missionary among the Indians, the Fathers caused another log chapel to be raised, an exact replica of the first, and, on May 3, 1906, the last burial of Father Badin took place, and his bones were placed in a tomb in front of the altar near the middle of this Chapel. A marble slab sunk in the floor over the tomb commemorates his life.

The history of Father Badin remains to be written. It is a duty that belongs to the Church in Kentucky, and to the Church in the United States, to bring out of obscurity this noted apostle of religion, and show him to the world with all his glory around him. There is no enigma in his life that needs remain so, and

there is no circumstance in it which does not admit of a light that will show him singularly unselfish, and animated with the highest sentiments of honor and religion. In order to give him his proper place in the history of the Church it will not be necessary to pull down another, for in the house of God there are many mansions, and Father Badin’s place has different appointments and different furnishings from that of any other. Who will rise to the occasion and confer this great boon on the Church of America ~ In the meantime, venerable Apostle of Kentucky, rest in peace!